As a child I wrote stories in booklets made of scrap paper haphazardly stapled together, a combination of words with crayon illustrations that made for a colourful—if not entirely comprehensible—storyline. By the time I was ten I fancied myself a journalist, pounding out short news articles on my dad’s old typewriter, covering the big events of my childhood: the crash of the space shuttle Challenger, or the malfunction of West Edmonton Mall’s Mindbender roller coaster.

As a child I wrote stories in booklets made of scrap paper haphazardly stapled together, a combination of words with crayon illustrations that made for a colourful—if not entirely comprehensible—storyline. By the time I was ten I fancied myself a journalist, pounding out short news articles on my dad’s old typewriter, covering the big events of my childhood: the crash of the space shuttle Challenger, or the malfunction of West Edmonton Mall’s Mindbender roller coaster.

Writing came easily, and it was fun. But all that changed as I grew up. I began to wonder if there was some formula that I could follow to make me a real writer. Some never-shared secret, locked away in the private notebooks of the successful writers I read so avidly.

To my surprise, I discovered that writers tend to share advice freely, and that the secret to joining their ranks isn’t that secret after all. The rules are there, clearly and consistently laid out in memoirs, books on the writing craft, and blogs. The only thing that’s required is that we follow them.

Some writers—like Jane Kenyon—focus on tending the muse by protecting your time and your inner life, replacing noise with the sound of “good sentences in your ears,” and walking—preferably by yourself. Others—like Amitava Kumar—include additional advice on how to structure your writing practice: write every day at the same time, and have a goal for each day; say no to external projects; finish one thing before starting another.

What all these methods have in common is that they treat writing as work: write every day, preferably at the same time, and have a writing goal. Avoid distractions. Dissect the books of authors whom you admire, to better understand how you can re-create their voice and eventually develop your own.

But when I interviewed freelance water policy researcher Korice Moir for a series on women nature writers talking about community, home, and the writing life, she said this: “I recommend [writing] books, but I don’t always follow their advice. Why don’t we feel more comfortable with our own writing voices—and what will we do about this?”

The trouble is that life isn’t a neat, orderly box—and writing advice isn’t a one-size-fits-all prospect.

Not everyone can be a full-time writer: I don’t have a spouse covering the bills, and when my freelance work takes over I have little control over the more creative aspects of my writing. I used to be an academic scientist, and had no time to write regularly, let alone at the same time each day. Now I have a chronic illness that limits my productive time, and its unpredictability means I can’t count on being able enough to write daily. Other people do shift work, have multiple jobs, or are caught up in the necessary tasks of caregiving. All of these things can affect a writer’s ability to adhere to fixed writing rules.

Then there’s the fear. What might I put on the page if given the opportunity? Do I really have anything to say that hasn’t already been said? And even if I do get something out, who will read it, anyway? Maybe writing is just a frivolous, selfish hobby that keeps us from our everyday duties. I have more pressing things to do: training the dogs, cleaning the bathroom, vacuuming the house, raking up leaves. Others depend on me and their needs come first.

Worse than the fear is the shame. Like making New Years’ resolutions, defining writing rules sets the trap of almost certain failure. I’m ashamed because I haven’t written every day, or because I’ve allowed myself to be distracted by Twitter, friends, TV… I begin to suspect that perhaps I’m not meant to be a writer if I can’t even complete a supposedly simple task of daily writing practice.

Annie Dillard’s famous quote rings in many writers’ ears: “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.” Amitava Kumar admits he was terrified that if he didn’t spend his days writing, then his life was wasted. But as Diana Saverin writes, “I could much sooner tell you the way I’d like to spend a life than the way I’d like to spend an hour.”

I’m learning to take a step back from the exhortation to write every day and look at the bigger picture: how I want—and am able—to spend my life. By accepting my limitations, I can apply that plentiful writing advice in the context of my own messy life. I remind myself that only I know how best to fit writing into my days; the maxims of others may not apply.

What I wholeheartedly agree with is the advice of most writers on the importance of making time to be present. Writing requires that we put ourselves on the page in the here and now – if we’re not present, if we’re checking Facebook or worrying about our next pay cheque, we won’t get anywhere on the page. While being present doesn’t happen instantly or all the time, one thing that’s struck a chord with me is Daniel José Older’s suggestion to let go of “should have” or “if only.” Then you can use that freed up mental space to settle down, settle in, and find your own writing process.

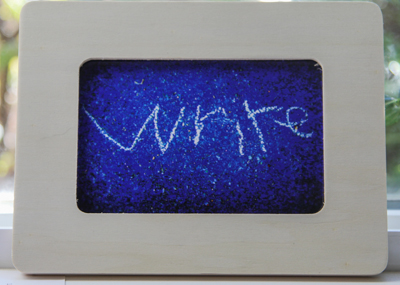

Ultimately, the best writing advice I’ve ever received came down to a single word, simply framed as a Christmas present from my nephew last year: “Write.”

Exactly how you go about it is up to you.

Thanks to Kimberly Moynahan for commenting on an early draft of this post.

Sarah Boon has straddled the worlds of freelance writing/editing and academic science for the past fifteen years. She blogs at Watershed Moments about nature and nature writing, science communication, and women in science. She is a member of the Canadian Science Writers’ Association and the Editors’ Association of Canada, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society in 2013. Sarah is also the Editorial Manager at Science Borealis. Find Sarah on Twitter: @SnowHydro.

5 comments

Very nicely put Sarah. I’m a woodworker at heart and feel the same constraints and self-imposed walls to following my craft. It sounds like you have opened the door a wee bit and got a peek at how you can make some time/space for your writing. Good to hear, hopefully it allows you to eventually push the door wide open and explore your writing as you see fit.

Thanks for sharing,

W

Well said, Sarah. There is a lot of advice out there and most of it makes the practice of writing look straightforward – “if only” the writer in question would sit down and write. I’m one of those who is more often than not pulled away to other elements of life – and then feel guilty. I empathize with your observations on the “supposedly simple” daily writing practice.